The Road: An Apocalyptic World in Three Songs

- Katherine Dahl

- Feb 28, 2024

- 3 min read

The apocalypse has been an object of fascination for humans—and the media—for years; whether it be zombies, nuclear wasteland, or just plain planetary destruction, we are constantly writing and thinking about what happens ‘at the end of the world.’ One of the most raw, difficult, and emotionally wrenching representations of the destruction of humankind is Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Published in 2006, the story focuses on only two characters: an unnamed father traveling with his unnamed son along an unnamed road in an attempt to reach the warmer climate in the south. The industrial world has been destroyed by an unknown catastrophe, and all that is left is the tattered remains of a human-run world in which the two characters must fight the cold, food scarcity, and an ashy landscape ingrained into the very air they breathe.

The ruination of nature is very clear in the novel, whether that be from the descriptions of the sky to the sea. There is no green grass or leaves, only gray ash and smog, which all exemplify the total annihilation of life on the earth. The first song for the novel is “The Landscape is Changing” by Depeche Mode because it describes how the natural world is falling to pieces. But, unlike the song, where “thousands of acres of forest are dying[,]” the world in The Road is already dead. The act of dying is in the past, making the story seem hopeless. The only things left breathing, the humans, become more beast than man due to the desperation of staying alive in a dead world.

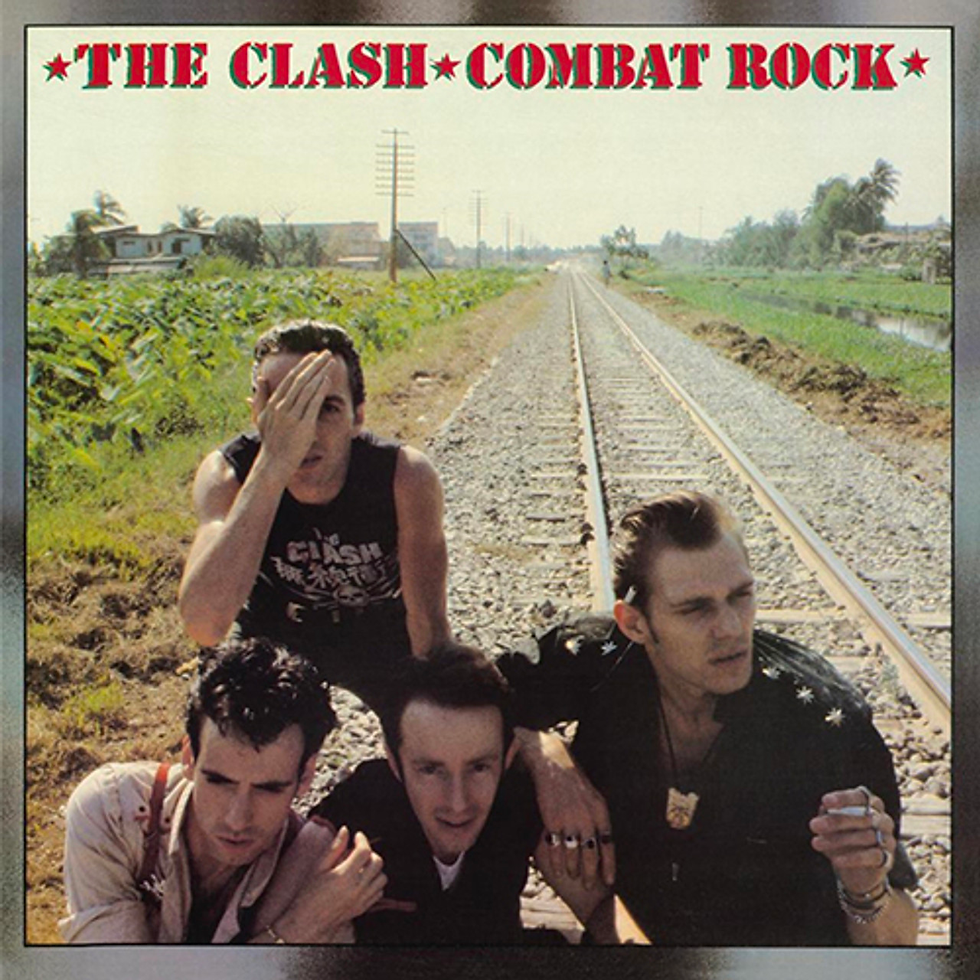

Safety is a fickle thing in The Road. Each time the father finds a refuge, the question of its lasting power is raised, and he forces himself (with his son) to continue moving on. In a perhaps more serious version of the message in the song “Should I Stay or Should I Go” by the Clash, the father must constantly choose between relative security or ongoing, anonymous movement. He knows that “if [he goes] there will be trouble” but staying would “be double” for fear of other wanderers coming upon their stash—and those other wanderers would be willing to kill (or worse) for supplies. In a time of commonplace murder and even cannibalism, there is no place for relief or peace, so the family must continue trudging on the road.

This constant movement is also part of why the father drives them towards the south and towards the ocean—not only is there the promise of warmer weather, but also of an unknown fate. The sea, something immutable and huge, represents hope throughout the novel. There is always the lingering feeling that maybe there will be something waiting for them at the shore. There is the hope that “Beyond the Sea” (like the song by Bobby Darin) there will be people, opportunities, or even a normal life. The “golden sands” of the father and son’s imagination is, in actuality, a gray beach of dead life and a dark sea. What was once “beyond a doubt” (at least in what they were telling themselves) the place they would find safety or discovery becomes yet another representation of destruction: an icy, lifeless bowl of black water.

Without spoiling the end, it becomes clear that The Road is a harsh book, and one that proposes humankind as desperate to survive at any cost, even if that cost is turning into what the boy calls ‘the bad guys.’ What separates the boy and his father from the rest of the humans is that they keep their humanity: they are ‘the good guys’ in a world full of bad. Yet, it raises the question of what is good and what is evil; can such a binary be created and enforced in a world where all other constructions have been deconstructed? McCarthy’s representation of the apocalypse goes beyond the wasted landscape or the bestial men scouring the world for food—it questions the relationship between a man and his son and what it means to be a family. What does family look like in a world where home-cooked dinner is a can of peaches or spam—if you’re lucky enough to eat that day? The Road poses questions that have no easy answers, and that is partially what draws us to it, including myself. I recommend you look for those answers, if you dare.

Runner-ups: “The Moon is a Harsh Mistress” by Linda Ronstadt, “Only the Ocean” by Jack Johnson, “Big Yellow Taxi” by Joni Mitchell.

_edited.png)

Comments